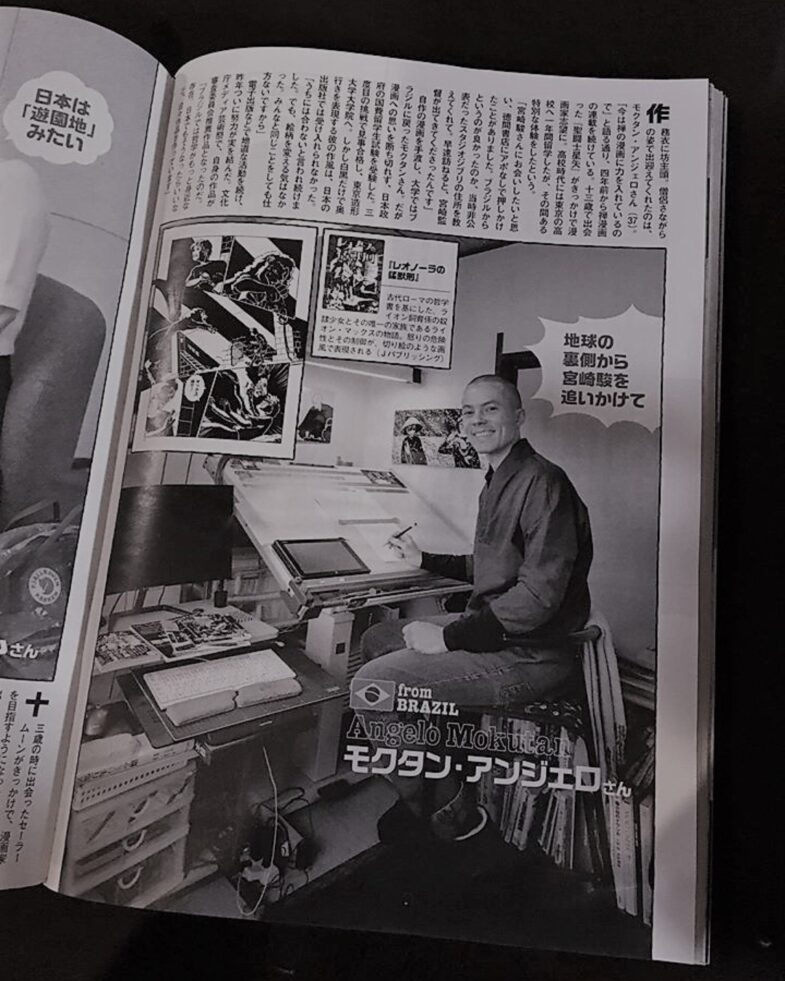

▲週間文春 2020年2月

▼コミックストリート

▼The Spendy Pencil

Interview with Manga Artist Angelo Levy by Lori Ono (Sept/2014)

▼Alternativa magazine

Updating Myths Through Manga

Based in Tokyo, the Brazilian artist Angelo Mokutan updates classical stories in the form of comics.

(By: Roberto Maxwell)

There is enormous prejudice against manga and it seems that even time hasn’t changed that. In Japan some schools still prohibit reading comics. What most people don’t know, however, is the hard work artists undergo in order to create these stories. There’s a good reason why these stories have become so popular. Many manga are strongly influenced by myths and legends, as old as humanity itself.

In the Brazilian Angelo Mokutan’s work, things aren’t much different. Having studied animation film making in Brazil and Japan, Mokutan is a studious creator. His purpose is to create works that contribute to his readers’ development as human beings. Just back from NYC, where he released “Little Riding Red Hood,” the first part of the trilogy “Once Upon a Time in Tokyo,” he revisits classical stories, setting them in the contemporary Japanese capital. Before releasing “Iara” – based on a Brazilian legend – and “Urashima Taro” – a Japanese legend adaptation – he chatted with Alternativa Magazine’s reporter.

When and how did you discover that you could make your own drawings?

It’s difficult to pinpoint a specific moment. Everybody draws in their childhood, but quits as a teenager, usually due to the frustration of not being able to draw realistically. In my case I just didn’t quit. Despite the exaggerated worship of original authorship so common in Euro-American cultures, human beings still learn essentially by copying and imitating other works. My case is no exception. So I think there was a gradual transition from this imitation phase to the phase I’m in now, where I’m looking more inside than outside in order to create and draw. Without a doubt, though, I must admit that the six years I spent studying fine arts and animation in university were very important to developing my current style.

What influenced and influences you throughout your work?

My favorite artists are Hayao Miyazaki for animation and Taiyou Matsumoto for comics. However I don’t copy their styles. Miyazaki teaches me about the rich poetry and deepness that can be appreciated by people of different ages, genders, nationalities, etc. Matsumoto, on the other hand, is inspiring for the freedom with which he draws. His stories are also very deep, and of the most refined artistic taste. I always listen to music when I’m working with drawings, so I get influenced by various composers as well: classical ones like Beethoven and contemporary ones like the minimalist Philip Glass and Hughes DeCourson, with his excellent fusing of classical and ethnic music.

What’s the difference between your work as an animator and as a comic draftsman?

Despite the many technical differences involved in animation and comics, my goal is the same for both: to retell stories that make people remember they are capable of much more than they imagine. For practical reasons, recently I’ve been focusing my production more on comics, but in the future, with a larger budget and more manpower, I’d like to get back into animation work.

Where did the idea for the project “Once Upon a Time in Tokyo” come from?

Myths, legends, and fairy tales are full of very deep messages and symbols. However they are frequently misunderstood due to the lack of importance given to them in our materialist culture. I greatly admire the mythologist Joseph Campbell, who wrote “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” and who served as George Lucas’s consultant on mythological matters during the creation of “Star Wars.”Campbell explains with simple and deep words the importance of such stories to humans’ psychological and moral development, and how much trouble could be avoided if we kept up this kind of education. I decided that I’d like to learn more about this subject and, from my humble position, contribute as an artist to the enrichment of people who seek this kind of content. All this has materialized in the project “Once Upon a Time in Tokyo,” which has been the subject of my research and work for the last five years.

How did you research the collection’s three legends in order to bring them to contemporary Tokyo? What did you think was important to preserve from the originals?

First I searched for the oldest versions of the stories to recover elements that were censored throughout the years, and compared them with stories from different places and ages. I noticed common characteristics, as Campbell had written about, and became concerned with preserving them. These are universal and timeless elements, and therefore compose the structure, the skeleton of the stories. Then I started thinking about how to retell the stories in contemporary Tokyo, adapting the symbols without changing their meaning. In this way, I invite the reader to re-read the stories, using more familiar language from the 21st century in the hope that the stories’ messages come closer to the surface, becoming more apparent to people.

What do these three stories tell people today?

Humans are born twice. The first birth, physical and external, is common to us all. The second, an inner birth, is optional and must be conquered. To remain alive for convenience, survival, leads nowhere. Being born a second time, humans start to better understand the world around them, seeing beyond appearances to the essence of things.

You’ve chosen a Brazilian, a Japanese and a European story. Does that have to do with your own multicultural life?

Yes, it’s a consequence of my multicultural life. My primary goal is to show how stories from different ages and places have common elements and are therefore very important to all humans.

(Dec/20/12, Japan)